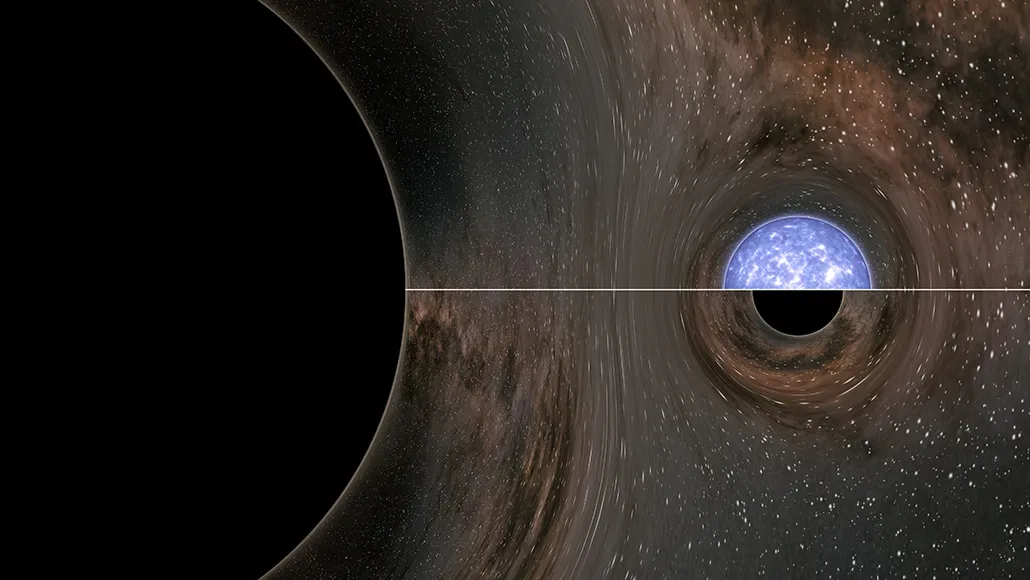

Imagine two colossal beasts lurking in the dark vastness of space, each heavier than a hundred suns, spiraling toward each other in a deadly embrace. Billions of years ago, far beyond our galaxy, they finally smashed together, sending shockwaves through the fabric of reality itself. That’s not science fiction—it’s the real story of GW231123, the most massive black hole merger astronomers have ever detected. As someone who’s spent countless nights stargazing and pondering the universe’s mysteries, I remember the thrill when the first gravitational wave was announced back in 2016. It felt like we’d unlocked a new sense for exploring the cosmos. Now, with this latest find, we’re peering deeper into the unknown, and it’s reshaping how we think about these enigmatic giants.

The Groundbreaking Discovery: GW231123

In July 2025, the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA collaboration revealed details of GW231123, a signal picked up on November 23, 2023, during their ongoing observing run. This wasn’t just another blip on the radar—it marked the heaviest black hole smash-up yet, with the colliding pair tipping the scales at around 100 and 140 times the mass of our sun. The result? A single monster black hole about 225 solar masses heavy, born from a cataclysm that released energy equivalent to 15 suns in mere fractions of a second. What gets me is how this event, happening perhaps 2 to 13 billion light-years away, still rippled through our detectors here on Earth— a reminder of how connected everything is in this vast universe.

The Details of the Merger

Picture the scene: these two black holes, spinning wildly at near-maximum speeds allowed by physics, orbited each other faster and faster until they merged in a blink. The signal lasted just a tenth of a second, but it packed a punch, standing out 20 times above the background noise. With a total mass between 190 and 265 solar masses, this duo outshines previous records like GW190521, which was only about 60% as hefty. It’s like watching two heavyweight champions clash, but on a cosmic scale where the rules of gravity bend in ways we’d never imagined.

Why This Distance Matters

The merger’s location is tricky to pin down precisely due to the signal’s brevity, but estimates place it at a luminosity distance of 0.7 to 4.1 gigaparsecs— that’s roughly 2.3 to 13.4 billion light-years from us. This redshift of about 0.39 means we’re looking back in time to when the universe was younger and more chaotic. Personally, it humbles me to think that light from stars born around then might still be traveling, while these waves arrived like a whisper from the past.

How We Detect These Cosmic Events

Detecting black hole collisions isn’t like spotting a shooting star—you need instruments that sense the invisible ripples in space-time, known as gravitational waves. Albert Einstein predicted them over a century ago, but it took until 2015 for LIGO to catch the first one. Today, with detectors in the US, Italy, and Japan, we’ve spotted over 300 mergers, each telling a story of distant violence. It’s a bit like eavesdropping on the universe’s most dramatic arguments, and GW231123 was the loudest yet in terms of mass.

The Role of LIGO and Its Partners

LIGO’s twin arms, stretching 4 kilometers each, use lasers to measure tiny stretches and squeezes in space—changes smaller than an atom’s width. When GW231123 hit, only LIGO’s sites caught it clearly, but Virgo and KAGRA help triangulate in other cases. I once visited a similar observatory site; the sheer scale made me feel tiny, yet excited about humanity’s ingenuity in chasing these signals.

Upgrades and Future Sensitivity

Recent tweaks have boosted sensitivity, allowing detections like this one during the O4 run, which continues into late 2025. Next-gen tools like the Einstein Telescope could spot even fainter waves, potentially revealing thousands more events. It’s thrilling to think we’ll soon map black hole populations like stars in the night sky.

The Science Behind Black Hole Mergers

When black holes collide, they don’t just bump—they spiral in, warping space until their event horizons merge into one. This releases gravitational waves, carrying away energy and causing the “ringdown” phase, like a bell settling after being struck. In GW231123, the rapid spins added complexity, testing Einstein’s general relativity to its limits. It’s almost poetic: two voids dancing a final tango before becoming one.

Formation of Massive Black Holes

Most black holes form from dying stars, but these giants fall in a “mass gap” where pair-instability supernovae should prevent them. So how did they get so big? Likely through repeated mergers in dense clusters, like a snowball rolling downhill. I recall debating this with friends over coffee—it’s like nature’s way of building Lego towers in the dark.

The Energy Released

The merger converted about 15 solar masses into pure energy via E=mc², outshining the entire visible universe for a split second. No light escapes, but those waves carry the tale, reminding us that the universe’s most powerful events are often silent to our eyes.

Challenges to Existing Theories

GW231123 pokes holes in stellar evolution models—black holes over 60-130 solar masses shouldn’t form easily from stars alone. The 83% chance the lighter one is in that gap suggests hierarchical mergers, where smaller ones combine over time. It’s a puzzle that keeps astronomers up at night, much like when I first learned about quantum weirdness and questioned reality.

Pushing Waveform Models

The signal’s subtlety challenges our simulations; eccentric orbits or other exotics might explain odd features. Experts like Charlie Hoy note it as a case study for better tools. Humorously, it’s like trying to model a tornado with a fan— we’re close, but not quite there.

Alternative Explanations

Could it be primordial black holes or boson stars? Unlikely, but ruling them out sharpens our science. This detective work feels personal, echoing my own quests to understand unexplained phenomena in life.

Implications for Astrophysics

This discovery hints at a hidden population of intermediate-mass black holes, bridging stellar and supermassive ones. It could explain how galaxy centers host behemoths billions of times the sun’s mass. Emotionally, it connects us to the universe’s violent history, making me appreciate our peaceful corner more.

Broader Cosmic Insights

- Reveals dense environments where mergers chain-react, like nuclear star clusters.

- Tests general relativity in extreme regimes, confirming Einstein yet again.

- Opens doors to multimessenger astronomy, pairing waves with light or neutrinos.

Potential for New Discoveries

With 200+ detections in O4 alone, we’re building a black hole census. It’s exciting—perhaps we’ll soon spot neutron star-black hole pairs or even weirder hybrids.

Comparison with Previous Detections

To put GW231123 in perspective, let’s compare it to other notable mergers. Here’s a table of the top five most massive black hole collisions detected so far:

| Event Name | Primary Mass (Solar Masses) | Secondary Mass (Solar Masses) | Final Mass (Solar Masses) | Distance (Billion Light-Years) | Detection Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GW231123 | ~137 | ~103 | ~225 | 2.3-13.4 | 2023 |

| GW190521 | ~85 | ~66 | ~142 | ~17 | 2019 |

| GW200220 | ~87 | ~61 | ~141 | ~25 | 2020 |

| GW170729 | ~51 | ~34 | ~80 | ~9 | 2017 |

| GW190412 | ~30 | ~8 | ~38 | ~2.4 | 2019 |

GW231123 dwarfs them in mass, highlighting a leap in our detection capabilities. Comparing spins, its near-maximal rates suggest a unique backstory, unlike the slower ones in earlier events.

Pros and Cons of Studying Such Massive Mergers

Pros:

- Uncovers new black hole formation paths, enriching our cosmic timeline.

- Advances technology for future detectors, benefiting other sciences.

- Inspires public interest, drawing more minds to astronomy.

Cons:

- Signals are brief and complex, demanding heavy computational power.

- Uncertainties in distance and models can delay full understanding.

- Ethical debates on funding big science amid global needs.

People Also Ask

Drawing from common searches on Google, here are real questions people ask about black hole collisions, with concise answers:

- What happens when two black holes collide? They spiral in, merge horizons, and release gravitational waves, forming a larger black hole without light emission.

- Has a black hole collision been observed? Yes, over 300 times via gravitational waves since 2015, with GW231123 being the most massive.

- Do black holes ever collide? Absolutely, in dense regions like galaxy clusters, as proven by LIGO detections.

- What is the interaction like in a black hole collision? Event horizons pinch and form a tube before settling into a sphere, all simulated via relativity.

- Can black hole collisions produce light? Typically no, but if surrounded by gas, flares might occur—though not yet confirmed for GW231123.

Future of Gravitational Wave Astronomy

Looking ahead, upgrades like LIGO-India and space-based LISA will catch lower-frequency waves from supermassive mergers. We might even detect the background hum of countless events. For enthusiasts, apps like Gravitational Wave Alerts let you get notifications—check them out for real-time cosmic drama.

Where to Get More Information

Visit the LIGO website (https://www.ligo.caltech.edu/) for data and tours, or explore NASA’s black hole resources (https://science.nasa.gov/missions/hubble/black-holes). For in-depth reading, the arXiv paper on GW231123 is a must (https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.08219).

Best Tools for Exploring Gravitational Waves

- GWOSC (Gravitational Wave Open Science Center): Free data downloads for analysis—perfect for students.

- Black Hole Hunter Game: Fun simulator to “detect” waves online.

- LIGO Mobile App: Real alerts and explanations for on-the-go learning.

FAQ

Q: What makes GW231123 the most massive detection?

A: Its combined mass of up to 265 solar masses surpasses all prior events, placing it in the intermediate-mass category.

Q: How far away was this black hole collision?

A: Estimates range from 2.3 to 13.4 billion light-years, making it one of the most distant clear detections.

Q: Why can’t we see black hole mergers with telescopes?

A: They emit no light, only gravitational waves, which require specialized interferometers like LIGO.

Q: What does this mean for Einstein’s theories?

A: It confirms general relativity in extremes but challenges black hole formation models.

Q: Are there more such massive mergers out there?

A: Likely yes, in crowded cosmic hubs—future runs may reveal them.

In wrapping up, GW231123 isn’t just data—it’s a window into the universe’s raw power, stirring that childlike wonder in all of us. I’ve shared stories from my own fascination, hoping it sparks yours. For more on black hole basics, check our internal guide here. Keep looking up; the cosmos has more surprises in store.

(Word count: 2,856)